Post Card from the "Museum of My Youth"

Communing with the freelance nightlife journalist version of me that emerged on the Lower East Side in the 90s out of a desire to belong.

Nearly every time I’ve visited lower Manhattan since moving upstate 18 years ago I’ve made pilgrimages to favorite old haunts. Most often I’ve gawked my old East Village apartment buildings (70 E. 7th St.; 326 E. 13th St.; 295 E. 8th St.) and marveled at the eerie sense I could just march in the front door and climb the crooked stairs (they all had crooked stairs) home, as if no time had passed and I still lived there.

Sometimes I’ve made interesting discoveries—like in 2007 when I figured out that filmmaker Michel Gondry had been the next tenant in the palatial but rundown E. 8th St. apartment Brian and I had gotten kicked out of in 2005, paying roughly five times the $1350 per month that we had. (Word on the street was Matt Dillon occupied it next.)

Wherever I’ve wandered on these visits, it’s been all about communing with old versions of myself—a ritual aptly described by the Libby character in Fleishman is in Trouble as returning “to the museum of my youth, trying to find the last place I’d seen myself.”

Another time, in 2021, I got to tour my E. 13th St. tenement after a young woman who was living there for two years at a special pandemic discount rate befriended me over email and invited me up. (She’d read Goodbye to All That and realized she was living in the apartment I’d described in my essay. I’m working on a longer piece about that, which I hope to publish elsewhere.) I was shocked by how little the building and apartment had been improved since the rent was boosted from the $722 I last paid to the ridiculous $3700 the apartment now commands.

Wherever I’ve wandered on these visits, it’s been all about communing with old versions of myself—a ritual aptly described by the Libby character in Fleishman is in Trouble as returning “to the museum of my youth, trying to find the last place I’d seen myself.”

A couple of weekends ago I scooched my museum tour a little further south, below Houston, to the Lower East Side. After November’s rejuvenating “artist date” I’ve sought reasons to spend more time in the city, and Elissa Bassist and Emily Flake’s excellent “Hysterical Women” variety show at P&T Knitwear Books & Podcasts on Orchard St., and the fantastic live episode of the Everything is Fine podcast at Caveat on Clinton St., perfectly fit the bill. I made a full weekend out of it: booked myself a cheap hotel room on Rivington St., made plans for meals with a couple of friend/colleagues (nearly all my friends are, in some capacity, colleagues), and scheduled my quarterly haircut with Julie at Twigs Salon.

Before the pandemic I did this kind of thing more frequently, usually tied to one of my weekend-long personal essay workshops at Catapult. (I’m still so sad and angry about the demise of Catapult.) Since then I’ve missed having explicit work excuses to justify the cost of a round-trip Trailways ticket, a hotel room, and meals out. But I’ve realized that most of my endeavors on these trips qualify as tax write-offs, and what’s more, these little excursions are good for my sanity. Even after 18 years aways, I still feel more alive in New York City than anywhere else. So I’ll be going in more often.

As I strolled around I thought a lot about the way freelance journalism frequently served as a “work excuse” in my mind, a passport, a way for me to inhabit spaces I never felt I belonged in—places I was curious about but which felt off-limits to me, most of all the nightlife scene.

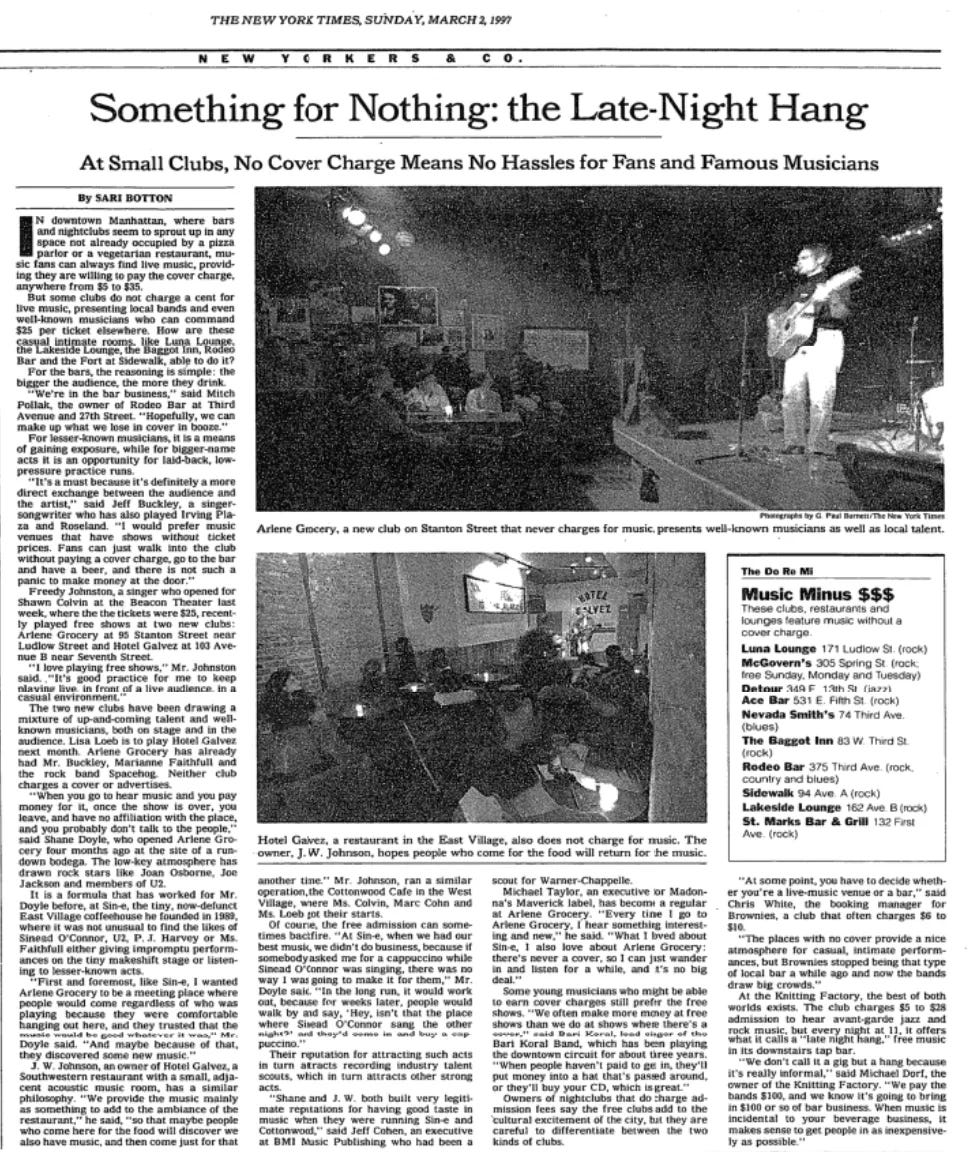

That weekend, in between events and meals, I took myself on a walking tour of the nightclubs I’d written about for The City section of the New York Times in the ‘90s (and the establishments and empty storefronts that have since replaced some of them), plus some other haunts. Arlene’s Grocery. The Mercury Lounge. Deanna’s jazz cafe, which was knocked down in the early aughts to make room for the very hotel I was staying in. The former Sunshine Theater, where a huge nightclub was planned and then vetoed by the community board and the State Liquor Authority. A toxic ex’s Essex St. apartment building, where I cohabitated with him for months here and there in the leanest of times, while I pimped out my own place for cash through a ‘90s AirBnb precursor called New York Habitat.

As I strolled around I thought a lot about the way freelance journalism frequently served as a “work excuse” in my mind, a passport, a way for me to inhabit spaces I never felt I belonged in—places I was curious about but which felt off-limits to me, most of all the nightlife scene.

In my teens and early 20s, as a sheltered daughter of clergy, I was discouraged from ever going to bars and nightclubs. In college I rarely went out, in part because the drinking age got raised on me after I was legal—twice—first from 18 to 19, then from 19 to 21. I also wasn’t terribly interested in drinking, something I no longer do at all. I just wanted to be allowed to go out with my friends, but after the drinking age went up, bouncers in Albany, where I attended school, got serious about barring those of use who were underage.

One weekend evening toward the end of my senior year, in the spring of ‘87, when I was finally 21 and legal, my dad called as I was on my way out to meet up with some people at The Lamppost or Washington Tavern or The Ginger Man, a wine bar—I can’t recall which. When I told him where I was headed, he freaked out. “A bar?! A bar?! Jennifer Levin went to a bar!” I still went, but it felt like some huge transgression, and not in a fun way.

This issue contributed to my feeling terminally unhip—a plight common to clergy kids. It’s practically a law of nature that my kind are rarely cool, unless you, like, drop out of school, run away from home, join a cult, go to jail. All I ever did was quit going to synagogue and get some tattoos, and I didn’t have the nerve to take even those wayward steps until I was well into adulthood. Oh, and I married goyim the second time around—someone who happened to have run away from home as a teen, first to Prince Edward Island, and later to Maryland. But while running away lent Brian a certain mystique with the kids at school when he returned home a year later, his experience really doesn’t confer any coolness onto me.

It’s practically a law of nature that clergy kids are rarely cool, unless you, like, drop out of school, run away from home, join a cult, go to jail. All I ever did was quit going to synagogue and get some tattoos, and I didn’t have the nerve to take even those steps until I was well into adulthood.

I have a piece in my memoir called “New York Cool” about how moving to the East Village served as my own personal Dork Rehabilitation Program, and all the ways in which I strived to reinvent myself there. Becoming a freelance journalist on the nightlife beat was a big part of that. A reporter’s notebook and pen lent me an air of legitimacy in a milieu where I felt like a complete fraud. They allowed me to peer into a scene I felt excluded from and observe how people interacted. How did one act casual and feel at home in a bar or nightclub? This was my primary investigation, beyond whatever angles I focused on in my articles.

Speaking of which, the Times has finally reinstated to its archives most of the pieces I wrote in those days, although for some reason, not all of them. For 17 years, the Times excluded from its archive pieces written by many freelancers like me due to a copyright dispute with the Authors Guild and other organizations that dragged on and on. (I didn’t see any money from the settlement.) I’m having fun rereading them now, and realizing what I was really after in pursuing that work.

In recent years, for various reasons, I’ve mostly given up on being a journalist in any official capacity. I now see myself more as an essayist and memoirist, although from time to time I’ll incorporate some reporting in what I write. I’ve come to feel much more comfortable in bars and nightclubs, although I do often feel as if I’m somehow trespassing in them. Maybe I’ll always feel that way. Honestly, I still feel like a dork no matter where I go. It is what it is, and it’s fine.

In other news…

Mark your calendars for Weds., May 17th at 7pm when Ken Foster and I will host a special edition of his Nightcap Reading Series at Mama Roux in Newburgh to celebrate the 10 year anniversary of the publication of Goodbye to All That. Lucy Sante, Lori Stone, Vanessa Mártir, and I will read.

Oh, good news. This week the other thing that was “eating me” finally got resolved, too. 🙏 I’m not going to write about it specifically other than to say that it involved a forensic accountant from the government scrutinizing my personal bank statements and transactions, even though I was not the party being investigated. Good times. (Can someone please inform my amygdala that my body no longer needs to be on high alert, so I can get off the anxiety-depression rollercoaster and get some sleep?)

Hey Sari's amygdala - chill out! Let her sleep!

I paid $400 a month for a similar apartment--mouse infested, bath in the kitchen, tiny bedroom--up in Hell's Kitchen in the late '80s. Pre-pandemic, I took my husband to see the building. The dumpster was still in the courtyard, and there were torn curtains in the windows. "Talk about squalid," he said. It hadn't changed much since I lived there, but I'm sure the rents are outrageous and rats still congregate under the dumpster.