I spent a fair amount of time this weekend searching through my house and garage for a few particular photos. So far I’ve failed to find them, and it’s driving me crazy. In the process, though, I happily relocated a few boxes and bags haphazardly stuffed with pictures taken throughout my 55 years.

I kicked myself for never organizing my photographs or placing them in albums. I’d always assumed there were only two reasons I’ve never done this: 1) It’s a family tradition. My mom has always kept her trove of old family photos loose, in big hat boxes from a time when people wore hats. It’s kind of fun to sift through ancient, familiar photos this way; coming up on them in random order makes the experience feel a bit fresh each time. 2) It’s too much tedious work.

Now I realize there’s a third reason: It’s too painful. I don’t want to construct too clear a visual narrative of difficult times in my life—my immediate family’s collapse; the step-family I was part of for six years before it dissolved and my step-siblings stopped being my step-siblings; my failed starter-marriage; my sort of train-wreck years when I made one sketchy boyfriend after another the center of my universe—nor too handy a catalogue of all the people lost along the way, those who’ve passed away, and those lost to strained or frayed connections.

I prefer to dip in now and then and sample just as much of the past as I can handle. The problem is, that makes it frustrating to try and find specific images when something happens to remind me of them. That’s where I am right now. Something happened, and it reminded me of a few photos, and for the life of me, I can’t find them, and I want to scream.

What happened is that an old friend died, and it has messed with my mind in a big way. My friend and I hadn’t been actively in each other’s lives for many years. The distance first took geographical form, after my friend moved far away. Then my friend became a parent, which involved moving to a whole other time zone I have never inhabited, and which has tested many of my friendships with people who became moms and dads. Finally, my friend got red-pilled, clashing with me and other liberal friends on social media in recent years, before getting off all the platforms, altogther.

(I’m being vague here because last week I made the tragic error of being too specific on social media, unwittingly feeding some online trolls in posts I’ve since deleted.)

Engaging with the red-pilled version of my friend was shocking, until it became annoying, and finally so dismaying I just couldn’t deal. Learning of my friend’s passing this week brought me back to that feeling of shock—to the conundrum of trying to square the person I once knew with the person my friend was turned into by the steady flow of misinformation that is destroying, well, everything in its wake. It’s made me wonder whether my friend was ever really the person I thought I knew. Was it all just an illusion? Did we only know so much about each other? Before Trump, how often did we take for granted that friends generally shared our political and philosophical views—especially friends who moved in the creative world right along with us?

In my effort to make sense of it all, I’ve found myself in a very nostalgic place, reviewing the years in our thirties when my friend and I were close. For the past week, I’ve been thoroughly obsessed with that time, replaying again and again certain conversations and interactions—and searching for some photos from times we spent together. It’s as if I’m trying to locate, to tangibly reconstruct that version of my friend, so that I can verify that the person I remember was real. Without that person to talk to, though, and without the photographic evidence of our time in each other’s company, it feels as if I’m chasing a ghost.

I was able to find a postcard my friend sent shortly after moving away—long before parenthood, and even longer before the red-pilling. It gave me a tiny bit of insight into my friend as a striving creative person, and made me reflect on what it means to strive in competitive creative fields for decades without achieving significant success, or the kind of success you once thought to be easily within your reach.

I don’t feel up for further explaining what I mean about that here, right now. Instead, I’m going to add an essay about this to my book. That feels like it will be a better, more thoughtful way to memorialize my friend.

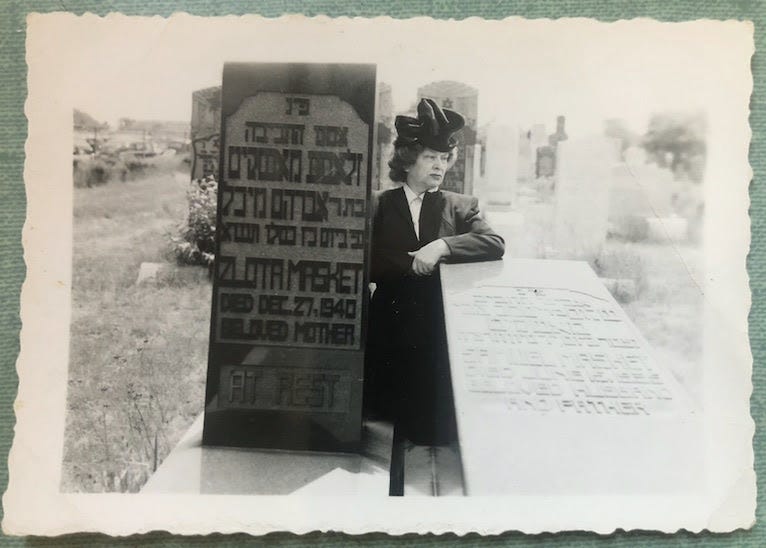

In other news, last week LitHub published a companion piece I wrote to go along with a moving photo essay by photographer Alexey Yurenev featuring images of elderly Jewish veterans of the Red Army, and the doors to their Brighton Beach apartments. I wrote about my own Russian Jewish ancestors, including my great-aunt Hasie, pictured here—in a photo I fell upon this weekend, as I searched for pictures of my friend: