The (Ugly) Butterfly Effect

What's a way in which (you hate to admit) someone changed your life for the better?

A writing prompt I occasionally toss out in my essay and memoir workshops is, “Write about a way in which (you hate to admit) someone changed your life for the better.”

In my life, there have been a few people who’ve fit that bill. The person among them who did the most for me was my maternal grandfather, George Masket, aka “Papa George.” He was a complicated man — or maybe not complicated enough — and there were disturbing aspects to our relationship, which is why I experience a mix of uncomfortable feelings each time I stop to acknowledge the ways in which he helped me get ahead.

🌟🌟🌟

My very first job in life was wrapping gifts at a bookstore in Oceanside, New York, for one month approaching the holidays in 1981, when I was 16. I started my second job just after that, working for my grandfather at his Seventh Avenue women’s apparel firm, "George Masket, Ltd.” on Saturdays during my junior year in high school, and intermittently on school breaks through college.

A cousin used to joke, “What do you do, pour Scotch all day?” In fact, that was a part of my job. Around 10:30am I’d fill the first tumbler with ice and Johnny Walker Black; I’d repeat that task several times before leaving at 5pm.

Obviously my grandfather was an alcoholic — and all-around glutton — who each day downed a fifth of Scotch, smoked four to five packs of cigarettes, and over-ate large quantities of fatty foods. He was 5’6” and weighed more than 300 pounds (his doctor couldn’t weigh him on a regular scale), and had a smoker’s cough so pronounced it could be mistaken for a death rattle. I used to insist that he was sharp as a tack at work despite his indulgence, but his business eventually went belly up, and he died broke. It’s a miracle he lived as long as he did, to 77.

🌟🌟🌟

Of course, pouring Scotch wasn’t all I did at George Masket, Ltd. I also answered phones, ran errands, straightened up the showroom after buyers from boutiques and department stores had visited, and did secretarial work in the office among a few hilarious old Jewish ladies. (In the computer system, they labeled deadbeat accounts “Nudnick.”)

At the end of each week, George would hand me a wad of $250 in cash, money I desperately needed to pay for college. As he was paying me, sometimes he’d make inappropriate comments about my looks and my body — an unpredictable mix of compliments, innuendos, harsh criticisms, and once, a shocking, racist remark about the size of my backside. He’d sometimes say those things when I entered his office to refresh his drink, too. Now and then he’d call me into his office with the singular, express purpose of remarking on my appearance. One day it would be, “My god, you’re gorgeous.” The next, it was, “You look like shit. Now get out of here.”

I kept my mouth shut. I needed the money. Also, I didn’t have any idea what would have been an appropriate thing to say, anyway. He was my grandfather, a man I’d been enamored with as a small child — when I’d sit on his lap and become intoxicated by his attention to me and the smell of the drink in his glass. When I was just a toddler, he’d have his tailors create miniatures for me of the clothes he manufactured, then show me off in them at Garment Center restaurants or the Long Island country club where he played golf. It made me feel incredibly special. After my grandmother died when I was almost 7 — and he remarried shortly after — he stopped being as attentive. I was at a loss for why, and craved his love and approval.

🌟🌟🌟

At some point during the first year I worked for George on Saturdays in high school, he made a generous offer: “I’m going to pay for college,” he said. “You can go wherever you want.” It was a relief because my parents had told me from the time they split up, when I was 11, that money was very tight and I would have to put myself through school.

I attended a college fair where I fell in love with Emerson College. It was an arts-oriented school, and I was an artsy kid.

I got home from the fair and called George’s apartment. When his wife answered, I rambled excitedly about this school I’d discovered, and how Papa had offered to pay for it. She was silent for a moment, then said, “I think that’s an awful lot for you to ask,” and hung up on me. Her response took my breath away. I never brought it up again. I kept working for my grandfather, anyway, and I put myself through college at a state school. Later, George would go on to make other grandiose promises and reneg on them, but I won’t bore you with them here.

🌟🌟🌟

The summer of 1986, between my junior and senior years at SUNY at Albany, I landed the Newsday internship. A car was required, but I didn’t have one. After grumbling about my suddenly not being available to work at his company that summer, my grandfather relented and generously rented me a car — a huge Chrysler New Yorker that had a handful of crack vials in the trunk (which smelled like vomit) — from a scary guy who looked like a mobster.

I thanked George profusely and apologized to him for bailing on him for two months, explaining that the internship was really important for me to take — and also that I hadn’t really expected to get it. My father and my college boyfriend had both pressured me to try for it, and at first I resisted. “I’m sorry,” I said, “but I’m a playwright.” Two plays I’d written at school had received staged readings, so I was feeling confident. Also, the application for the Newsday internship had a disclaimer noting they received about 3,000 applications each year for about 25 spots, so you shouldn’t count on it.

But I was a journalism minor, and the application intrigued me. In addition to a 400-word news item and a 1000-word feature, you had to write a 750-word profile of yourself in the third person. I of course profiled myself as a playwright. I was shocked when I received my acceptance letter. Appropriately they put me on the arts desk, working under Caroline Miller. I expected to be assigned menial tasks, but instead they threw me in the deep end, sending me to cover arts events and interview people in theater, film, television, dance, and fine art. I was instantly hooked.

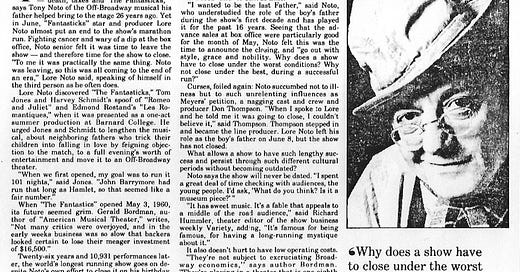

One of my first clips. ^^^

After my Newsday internship, in my senior year, I was able to get a lot of freelance work writing arts pieces for the Albany Times Union and a now-defunct alt weekly magazine called Metroland. I put the money I earned toward tuition, but I couldn’t have done any of that work — or held my two other part-time jobs that year, processing claims at Blue Cross/Blue Shield and teaching Sunday School at a Reform synagogue — if my grandfather hadn’t helped me out by making the first year of payments on the used 1981 Honda Prelude I bought.

Was this the cutest car or what? ^^^

Having that car was instrumental in my ability to pay for my senior year, and to get going in my career as a writer. It was a real game-changer.

I’m indebted to George for the first year of payments, and for so much else — despite my repulsion every time I recall the inappropriate and disgusting things he said to me, and his broken promises.

🌟🌟🌟

Letter of Recommendation: Jami Attenberg’s #1000wordsofsummer

Some of the material I’m mining for this newsletter was generated last year as part of novelist Jami Attenberg’s #1000wordsofsummer two-week writing commitment, which I loved. She’s getting ready to launch it again, June 17-July 1, and I can’t recommend participating in it highly enough. Basically you sign up for Jami’s newsletter — which is filled with encouragement form Jami and some other writers — and commit to writing 1000 words a day during that time. I did it during a particularly busy period, and it was so great to discover that I actually could make time for my own writing anyway. I stayed up late, got up early, and realized I could bang out 1000 words in under an hour sometimes. Now I’m putting the writing I generated to good use.