"What Do You Want to Lie About?"

What I owe to a question posed by author—and now MacArthur Genius Grant recipient—Kiese Laymon. Plus: Some spots left in my Catapult anthology workshop starting tonight.

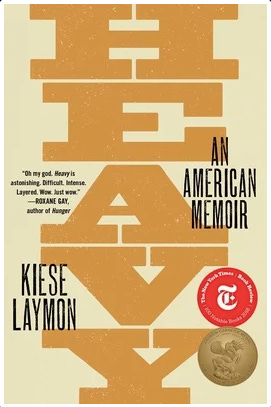

Yesterday the MacArthur foundation announced its Class of 2022 Genius Grant recipients, and I was thrilled to see author Kiese Laymon among them. I’m a big fan of Laymon’s work. His memoir, Heavy, is among the best I’ve ever read—gripping, eye-opening, incredibly moving. I devoured the whole thing in one day, which is rare for me, as I’m a slow reader.

In the book’s opening passages, Laymon comes clean to readers about the ways in which he’d wanted to lie to them rather than tell the painful truth about his difficult childhood, the family dynamics that made it difficult, his experiences with obesity and body dysmorphia, and with performing for the white gaze. “I did not want to write to you,” he writes. “I wanted to write a lie.”

I remember reading this and thinking it was a brilliant craft choice to begin a personal narrative with a nod to an inherent challenge for memoirists: fighting the inclination to present ourselves and our lives in a more glowing light than matches reality. A common fear among memoir writers, especially those starting out, is that they’ll come off as unlikable to readers if they reveal themselves warts and all. I’ve encountered that fear while working with ghostwriting clients, writers I’ve edited, and students of mine. What I try to convey to them is that what many readers really want is a main character who is as real and flawed as they are. They want to read the writing of someone who is human, someone who articulates what it means to be human—including the ugly parts of that—in such a resonant way that they can understand their own complicated humanity in a new light.

Shortly after the book came out, Laymon sparked a related discussion by posting this question to writers on social media: “What do you want to lie about?” It’s not only a great question for writers of first person, but a great writing prompt for us as well.

I began asking my essay and memoir students that question—crediting Laymon, of course—not so much as a prompt as a form of guidance. It was my way of trying to lead them in the directions of: digging deeper emotionally; interrogating the ways they might choose to present themselves and their lives; and choosing more complicated stories from their lives—ones in which they might not have played flattering roles—to feature in their work.

In 2020 and 2021, when it was time to work on my own memoir, I posed Laymon’s question to myself again and again. I’d like to believe that led me toward greater honesty about my own unfortunate choices and behaviors and tendencies, and made And You May Find Yourself… a better book. One of the most consistent compliments I receive from readers is that I was unflinchingly candid about my own mistakes and foibles. It makes me proud when people tell me that. That was one of the hardest parts of writing my book.

Last week, when I was in (virtual) conversation with Megan Stielstra via Oblong Books in Rhinebeck, she told me that she picked up on Laymon’s influence right off the bat. She read aloud the opening lines of my book:

Then she asked me about the impulse to tell on myself right out of the gate—as in, not only tell the truth, but come clean about first fudging the truth—and whether I was aware of that aspect of Laymon’s work. I told her it was the direct result of asking myself Laymon’s question, day after day, throughout the writing of the entire book.

I owe him a huge debt of gratitude for those seven words. Thank you, Kiese. 🙏 And congrats on the MacArthur grant. 🙌🏼

In other news…

This is obviously very last-minute, but there’s a spot left in my four-week Catapult anthology pitching workshop that starts tonight at 8:30 eastern.

This is a brilliant writing exercise! Thank you!